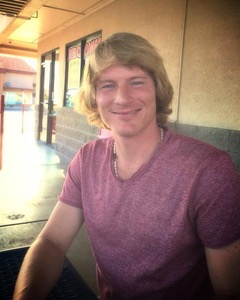

About five years ago I captured this photo of my son Ryan walking in downtown Phoenix. If you look closely you will see a homeless man sleeping on the ground by a trash can.

I couldn't help but notice the similarity in that man's clothing and my son's. I thought "There but for the grace of God go I." Followed by the thought, "But where is God's grace for that man on the ground?" I was troubled by that thought until I found a poem titled "Judge Not."

Judge not; the working of his brain

And of his heart thous canst not see;

What looks to thy dim eyes a stain,

in God's pure light may only be

A scar, brought from some well-won field,

Where thou wouldst only faint and yield.

The look, the air, that frets thy sight,

May be a token that below

The soul has closed in deadly fight

With some internal fiery foe,

Whose glance would scorch thy smiling grace

And cast thee shuddering on thy face!

The fall thou darest to despise...

May be the angel's slackened hand

Has suffered it, that he may rise

And take a firmer, surer stand:

Or, trusting loss to earthly things,

May henceforth learn to use his wings.

And judge none lost, but wait and see

With hopeful pity, not disdain;

The depth of the abyss may be

The measure of the height of pain,

And love and glory that may raise

This soul to God in after days!

Adelaide Anne Procter 1825-1864

There was a period of time when my son was very ill and sometimes homeless, relying on the compassion and generosity of strangers, asking for change to buy himself something to eat or drink. Today my son is the healthiest he has been in over 10 years. He's able to go to work and earn a paycheck.

I was worried about how he would use the money when he received his first paycheck. Yesterday I gave him $40 dollars to have in his new wallet. Today he had $7 dollars left. He spent his money buying treats and food for his friends in the group home. He remarked about how good it felt to be nice and do something nice for others.

Tonight we celebrated his 31st birthday at a seafood restaurant. During dinner, Ryan told me that, earlier in the day, he'd given a man on the street a handful of change because he remembered, when he was in that man's shoes, asking others for change.

Once again, I'm so grateful and amazed. It's by the grace of God, doctors, medication, and unconditional love that my son, who's suffered for so many years with severe mental illness, has come out the other side.

And yet he remembers, "There but for the Grace of God go I."